Full HTML

Omphalopagus parasitic twin: a case report and literature review

Ramdhani Yadav1, Asjad Karim Bakhteyar1, Rupesh Keshri2, Digamber Chaubey3, Sandip Kumar Rahul2

Author Affiliation

1Pediatric Surgeon, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar,

2Pediatric Surgeon, Department of Paediatric Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Deoghar, Jharkhand,

3Pediatric Surgeon, Department of Paediatric Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India

Abstract

Parasitic conjoined twins arise from the embryonic death of one twin, whose body parts remain vascularized and attached to the primary twin. Parasitic twins are rare and present unique challenges regarding the location of their attachment to the autosite and shared organs. In this case report, we describe the presentation and treatment of a parasitic omphalopagus twin that shared its liver with the autosite left liver lobe. The condition was not recognized before delivery, most likely due to the lack of prenatal care in the remote rural area to which the patient belonged. After a vaginal delivery, the twins were referred to our tertiary center, where a successful separation of the parasitic omphalopagus twin from the autosite was achieved.

DOI: 10.32677/yjm.v3i1.4404

Keywords: Autosite, Embryonic death, Omphalopagus, Parasitic twin

Pages: 48-50

View: 10

Download: 13

DOI URL: https://doi.org/10.32677/yjm.v3i1.4404

Publish Date: 11-05-2024

Full Text

Introduction

Parasitic conjoined twins result from the embryonic death of one twin that leaves its body parts vascularized by the primary twin (Autosite) and attached to it. [1, 2] They are very rare with an estimated incidence of less than one in one million births. [2, 3] Ambroise Pare is said to be the first to have described a headless twin with its body attached to the abdomen of its twin counterpart in the 16th century. [4] Following that, isolated case reports, series or a few reviews of these cases have been the only means to draw important conclusions about the parasitic twins, their types, and clinical features. The parasitic portion often has developed fetal parts and can be attached to the Autosite at one of the eight sites and accordingly can be assigned a name (thoracopagus, omphalopagus, craniopagus, cephalopagus, parapagus, ischiopagus, pyopagus or rachipagus). However, these eight sites represent only the more frequent attachment sites and several other sites can be involved with variations in the organs shared between the Parasite and Autosite. Being a rare entity with heterogeneous anatomy, its etiology and other aspects are still unknown and it has been recommended to report all such cases. [5] The presentation and management of a case of omphalopagus parasitic twin is discussed in this report.

Case Report

A one-day-old-male patient, weighing 3.4 Kg, presented with a parasitic twin attached to it. He was born of normal vaginal delivery at term to a 32-year-old Para 3. This delivery was carried out at a primary health care center near the patient’s village in a remote rural region but there were no complications of labour or any significant perinatal events. There was no significant antenatal history and an early third trimester antenatal ultrasound did not report the condition.

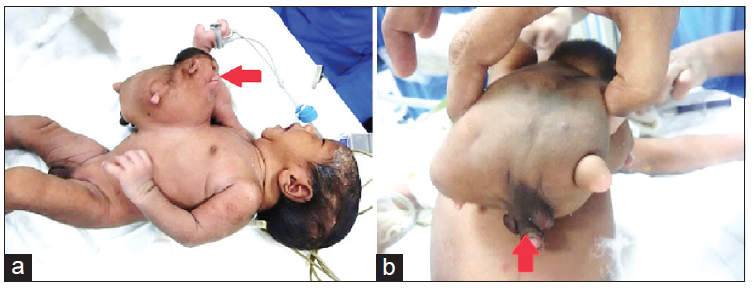

On gross examination, a small incompletely formed male baby of size 10 X 7cm was attached to the normal baby with point of attachment at abdomen (omphalopagus), having ill-developed face, developed bilateral ears and eyes, thorax, abdomen, genitalia but with rudimentary limbs [Fig 1a and Fig 1b]. On Ultrasound evaluation, they had separate gastrointestinal tract but shared left lobe of liver. This anatomy was confirmed by contrast enhanced tomography of the abdomen and chest. The echocardiogram of the Autosite was normal.

Figure 1: (a) Omphalopagus parasite with deformed face, but conspicuous ears, eyes, thorax, abdomen, genitalia, and limb buds (red arrow). (b) Omphalopagus parasite with well-formed genitalia and rudimentary lower limb buds (red arrow)

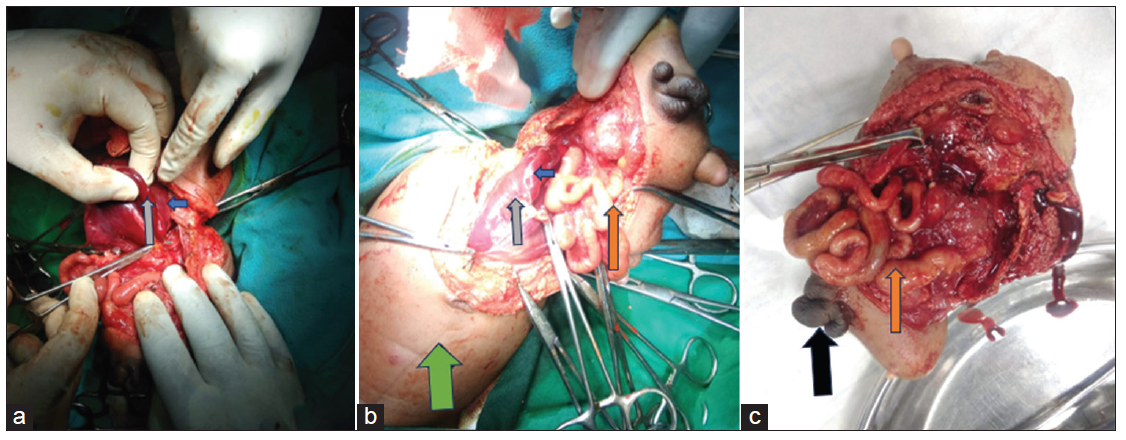

Parasitic twin was separated under general anesthesia. Intra-operatively, separate gastrointestinal tract was seen and left lobe of liver was shared; interestingly the parasitic twin had its own gall bladder with a separate biliary drainage towards the bowel of the parasitic twin [Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c]. The lower ribs on the right side were also attached to the parasite’s ribs and this required division towards the parasite’s side. Excision was done successfully [Fig. 2c]. Post-operative period was uneventful. After separation, the normal child (autosite) had uneventful follow-up and normal growth.

Figure 2: (a) The intraoperative picture where shared liver of the parasite (blue arrow) with the left lobe of the autosite (gray arrow) is demonstrated. (b) The intraoperative picture with similar details and well-formed intestines (orange arrow) in the parasite. Green arrow indicates the autosite. (c) The parasite with well-formed intestines (orange arrow) and external genitalia (black arrow)

Discussion

Heteropagus twins are rare and have varying presentation depending on their site of attachment and the organs they share. Isolated case reports or case series form the bulk of the related literature. Spencer et. al. found 157 cases reported over 125 years in his review article in 2001. [6] Sharma et. al. reported 39 cases over ten years in their review of heteropagus twins described in English literature. [2] Dejene et. al. reported five cases at their center over a period of nine years.[7] In a recent review by Mathur et. al., 120 cases of Heteropagus twins (including six at their two centers) were reported; Rachipagus was the most common (41.67%) while Omphalopagus was the next common variety (38.33%); limbs were formed in as many as 62.5% cases and 14.2%autosites had congenital heart disease. [8] Our case was an omphalopagus parasite with well-developed eyes, ears, external genitalia, gastrointestinal tract with gall bladder but had rudimentary limbs. The Autosite did not show any cardiac anomaly.

The pathophysiology of parasitic twinning is still unknown. The theory of abnormal twinning [9, 10] and that the twins are universally monozygotic have been challenged by cases where female Autosite had Parasites with presumed male external genitalia. [7, 11] Contrary to the fission mechanism which explains most of the Parasites described in literature, Logrono et. al. described Heteropagus twins after fusion of two embryos, where they conclusively demonstrated dizygosity using DNA typing. In their case, the parasite had perpendicular orientation to the autosite, which had semblance to mares where abnormal embryonal polarity led to resorption following early fusion. [5] So, both fission and fusion mechanisms can account for parasitic conjoined twins. For rachipagus, faulty secondary neurulation in a closed neural tube has been proposed where overproduction of neural tube fluid can leak into the subcutaneous tissue, thereby differentiating into various types of tissues.[12]

Heteropagus twins are associated with unique challenges in antenatal detection, obstetric management, imaging issues to delineate their anatomy, timing of surgery with respect to age and presentation, difficulty in separation, management of associated malformations in the Autosite and outcomes. Antenatal detection of such cases has been poor and only a few cases reported in literature have been detected on a prenatal ultrasound. However, if detected parasitic twins should be differentiated from other anomalies which have poor prognosis. Being unusual and associated with variable outcomes due to different associations and risks during delivery, ethical considerations for continuation of such pregnancies exist when detected antenatally. However, as these cases have good outcomes, continuation of pregnancy is recommended. Fetal echocardiography is recommended because a subset of these patients has associated cardiac anomalies. Meningomyelocoele and Omphalocoele are the other commonly reported associations which can cause long-term morbidities. [8, 13] Individual anatomical configuration and position of the parasitic twin along with weight mostly determines the mode of delivery when compared to the isolated weight of the Parasite. [8] Parental counseling regarding the outcomes is very important considering their anxiety, and the risks involved in managing such cases. Timing of surgery is as soon as possible after birth; but often patients are brought late to the hospital leading to delayed surgery. Non-detection during antenatal period, unsupervised non-institutional delivery and delayed presentation to the hospital leading to delayed surgery are often seen in developing and poor countries like ours where health care services are not uniform and often inaccessible to the poor. These factors lead to improper management and several complications. Implementation of universal health coverage programs ensuring antenatal, natal and post-natal care would help detect and manage all these cases at institutions capable of operating upon such children.

Because most of the parasites usually do not share organs with their autosites, ultrasound, computed tomograms or magnetic resonance imaging often suffice to delineate the anatomy to guide surgical separation which is then easy. Echocardiography of the Autosite is recommended due to the possibility of cardiac malformations. In our case, ultrasound and computed tomogram could reveal the anatomy and echocardiography was normal. Long term outcome after successful surgery is usually good. However, associated anomalies determine the future morbidities and mortality has been reported mostly secondary to major cardiac anomalies. In a review of 120 patients, Mathur et. al. reported mortality in 10% of the patients.[8] Antenatal detection, institutional delivery and multidisciplinary care are required for optimal management. [4]

Conclusion

Parasitic twins represent a heterogeneous group with variable anatomy and embryology. Proper management must include a multidisciplinary approach for antenatal detection, delivery, perinatal care, and surgical management with rehabilitation. Early detection and timely surgery lessen complications and allay parental anxiety. Their separation may be an easy or tedious process, depending upon the site of attachment and what structures are shared.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from parents for the publication of this case report and all associated images.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the completion of this work. The final manuscript was read and approved by all authors

References

- Satter E, Tomita S. A case report of an omphalopagus heteropagus (parasitic) twin. J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43: E37–9.

- Sharma G, Mobin SSN, Lypka M, et al. Heteropagus (parasitic) twins: a review. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:2454–2463.

- Edmonds LD, Layde PM. Conjoined twins in the United States, 1970-1977. Teratology. 1982; 25:301–308.

- Daronch OT, Rigolon LPJ, Moraes IP, et al.. Onfalopagus parasitic fusioned twin: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023 May; 106:108129.

- Logroño R, Garcia-Lithgow C, Harris C, et al. Heteropagus conjoined twins due to fusion of two embryos: report and review. Am J Med Genet. 1997; 73:239–243.

- Spencer R. Parasitic conjoined twins: external, internal (fetuses in fetu and teratomas), and detached (acardiacs). Clin Anat N Y N. 2001; 14:428–444.

- Dejene B, Negash SA, Mammo TN, et al. Heteropagus (parasitic) twins. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2018; 37: 44-49.

- Mathur P, Sharma S, Mittal P, et al.. Heteropagus twins: six cases with systematic review and embryological insights. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022; 38:963-983.

- Fujimori K, Shiroto T, Kuretake S, et al.. An omphalopagus parasitic twin after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2004; 82:1430–1432.

- Hwang EH, Han SJ, Lee J-S, et al. An unusual case of monozygotic epigastric heteropagus twinning. J Pediatr Surg. 1996; 31:1457–1460.

- Chadha R, Lal P, Singh D, et al. Lumbosacral parasitic rachipagus twin. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41: e45–8.

- Pandey A, Singh S P, Pandey J, et al. Lumbosacral parasitic twin associated with lipomeningomyelocele: a rare occurence. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013; 49:110–112.

- Hailu SS, Solomon DZ, Gebremedhin YG, et al. Dorsolumbar parasitic twin associated with lipomyelomeningocele: a case report from a tertiary teaching hospital, Ethiopia, East Africa. Radiol Case Rep. 2022; 17(10):3820-3824.