Full HTML

Novel Biomarkers for Acute Kidney Injury: Diagnostic Profiles, Etiology-Specific Applications, Prognostic Impacts, and the Path to Precision Medicine: Bridging the Clinical Action Gap—Review

Elmukhtar Habas1, Aml Habas2, Amnna Rayani3, Ala Habas4, Khaled Alarbi5, Eshrak Habas6, Mohamed Baghi5, Mohammad Babikir7, Abdelrahaman Hamad8, Almehdi Errayes9

Author Affiliation

1 Senior Consultant, Hamad Medical Corporation, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

2 Specialist, Open Libyan University, Tripoli, Libya

3 Professor, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya

4 Tripoli Central Hospital, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya

5 Associate Consultant, Hamad Medical Corporation, Hamad General Hospital,

Doha, Qatar

6 Tripoli University Hospital, University of Tripoli, Tripoli, Libya

7 Medicine Specialist, Hamad Medical Corporation, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

8 Consultant, Hamad Medical Corporation, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

9 Senior Consultant, Hamad Medical Corporation, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar

Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) remains a substantial clinical challenge, affecting approximately half of all critically ill patients and is associated with a high risk of mortality, need for dialysis, and progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD). Traditional diagnostic methods, which rely on urine output and serum creatinine (sCr), are non-specific and delayed, thus missing the crucial window for early intervention. New urine and plasma biomarkers, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP), interleukin-18 (IL-18), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 ([TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7]), and C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14), have become effective tools for risk assessment and early detection over the past decade. With diagnostic accuracy superior to creatinine, these biomarkers allow for the identification of AKI within 2 to 12 hours, as they represent tubular stress, damage, and healing processes. Multi-marker panels further enhance diagnostic performance, particularly in complex clinical scenarios such as sepsis and heart surgery. Etiology-specific biomarker patterns are now well-delineated: minimal elevations in prerenal conditions may guide safe fluid management, whereas sustained increases in intrinsic AKI suggest poor recovery and may necessitate renal replacement therapy (RRT). Biomarker-guided interventions have been shown to reduce the incidence of severe AKI by 15% to 30% in high-risk populations. Emerging biomarker types that have the potential to improve early detection and prognosis accuracy include filtration surrogates, oxidative stress indicators, microRNAs (e.g., miR-21, exosomal panels), and inflammation/repair biomarkers. Despite these advancements, difficulties remain, including inconsistencies in testing, high costs, limited data on juvenile and postrenal AKI, and a “clinical action gap” where biomarker findings have not been reliably linked to evidence-based therapies. The integration of artificial intelligence with point-of-care diagnostics has significant potential for future clinical applications. This review consolidates current data to illustrate how emerging biomarkers are transforming thetreatment of AKI from a reactive diagnosis to a proactive, precision-oriented strategy.

DOI: 10.63475/yjm.v4i3.0226

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, biomarkers, NGAL, TIMP-2, IGFBP7, prognosis, precision medicine, artificial intelligence

Pages: 514-525

View: 1

Download: 6

DOI URL: https://doi.org/10.63475/yjm.v4i3.0226

Publish Date: 31-12-2025

Full Text

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a critical condition marked by a swift deterioration in renal function, impacting 20% to 50% of hospitalized individuals and exceeding 50% of admissions to intensive care units (ICUs). [1,2] Etiologies include prerenal factors (e.g., hypovolemia, sepsis), intrinsic factors (e.g., acute tubular necrosis [ATN], nephrotoxin exposure), and postrenal factors (e.g., obstructive uropathy), all necessitating timely diagnosis to reduce negative outcomes such as mortality, renal replacement therapy (RRT), and progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD). [3] Conventional AKI diagnosis depends on serum creatinine (SCr) levels and urine output, which are delayed by 24 to 48 hours following the onset of injury and are insufficient for identifying subclinical damage. [4] The diagnostic delay hinders early intervention, resulting in mortality rates of 20% to 25% in severe cases and longterm renal dysfunction in up to 30% of survivors. [1,5]

Recent advancements in AKI diagnostics have been marked by the introduction of novel biomarkers that indicate tubular damage, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2/insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 ([TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7]), liver-type fatty acid-binding protein (L-FABP), interleukin-18 (IL-18), and C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14). [6] Markers indicating tubular damage, cell cycle arrest, or inflammation enable detection within hours post-injury, with area under the curve (AUC) values frequently surpassing 0.80 to 0.95 in high-risk contexts such as cardiac surgery and sepsis. [7,8] According to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, these markers provide prognostic insights that guide precision interventions by predicting the need for RRT, the persistence of AKI, and the progression to CKD, in addition to early diagnosis. [9] With AUC values of 0.95 for the early identification of AKI, recent meta-analyses have shown that multi-biomarker panels provide improved sensitivity and specificity compared to SCr alone. [8,10]

This review, utilizing data from recent clinical trials published between September 2022 and September 2025, examines the diagnostic characteristics of emerging biomarkers and their impact on outcomes in prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal AKI etiologies. This review examines the diagnostic characteristics of emerging biomarkers and their impact on outcomes across AKI etiologies. However, a major translational challenge persists: the “clinical action gap,” where biomarker identification of high-risk patients has not yet been reliably linked to evidencebased therapeutic interventions. Clarifying this gap and exploring pathways to bridge it are essential for realizing the promise of a proactive, precision-oriented strategy in AKI care. The evidence for this review was gathered through searches of PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Google Scholar utilizing terms such as AKI, NGAL, KIM-1, TIMP-2, IGFBP7, L-FABP, IL18, CCL14, prerenal, intrinsic, postrenal, prognostic roles of AKI biomarkers, AKI progression to CKD biomarkers, and AKI marker and RRT.

BIOMARKERS FOR AKI The predictive value of SCr and urine output is limited by delayed rise, limited specificity, and the inability to identify subclinical impairment, which has necessitated the development of innovative biomarkers that reflect pathophysiological mechanisms in AKI. [4,11] Markers measured in urine or plasma indicate tubular stress, damage, inflammation, or cell cycle arrest shortly after an insult, enabling risk stratification before any observable functional decline. [12] By 2025, meta-analyses of more than 100 studies have confirmed NGAL, KIM-1, [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7], L-FABP, IL-18, and CCL14 as highly reliable biomarkers. Meanwhile, proenkephalin A (PENK) and dickkopf-3 (DKK3) are emerging as important indicators. [8,10,13] These biomarkers reflect distinct, early pathophysiological pathways. NGAL, upregulated in tubular cells after injury, is a very early marker, with levels rising in urine or plasma within 2 to 6 hours. [7,14]

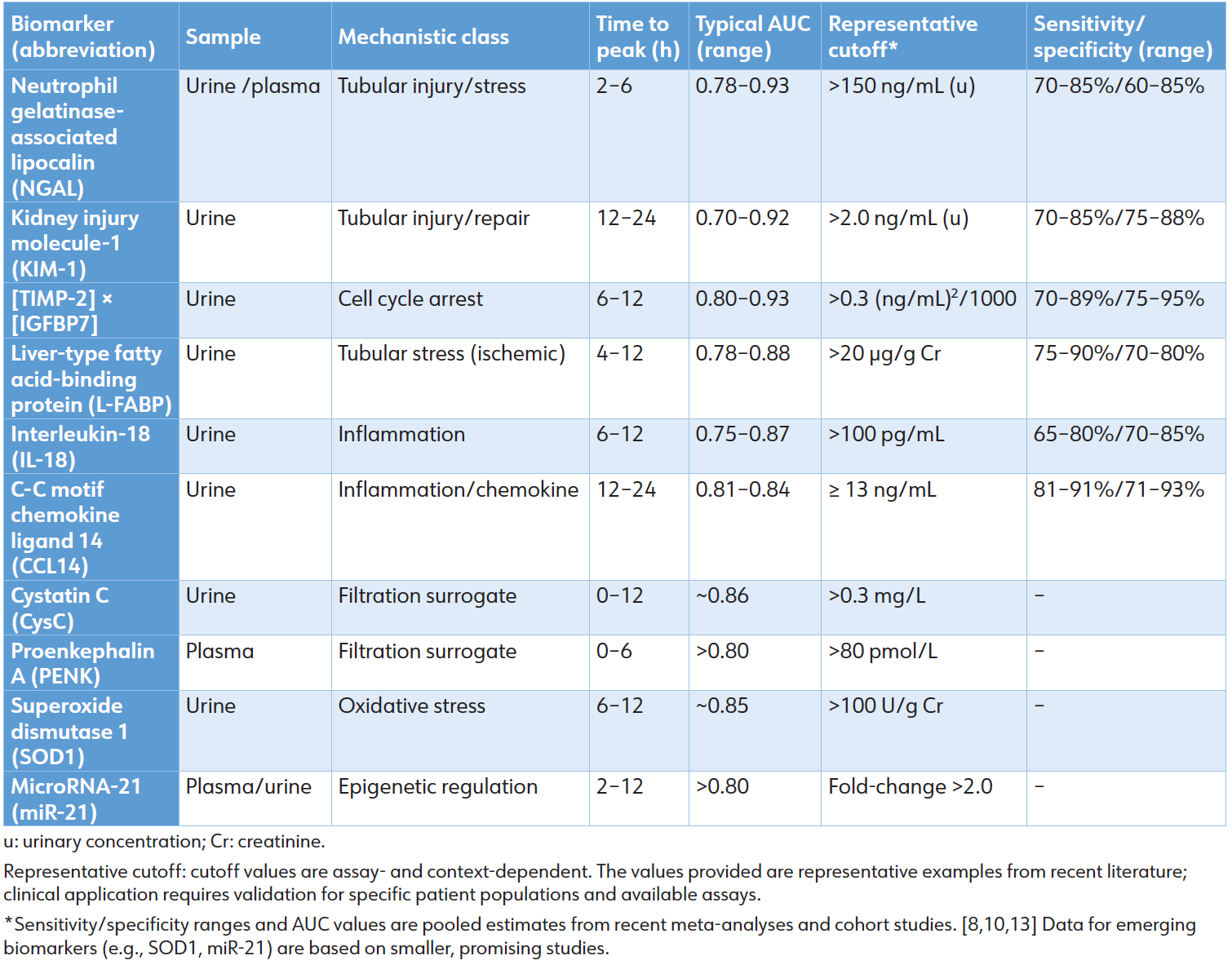

KIM-1, a proximal tubule transmembrane glycoprotein, signifies dedifferentiation and repair, peaking at 12 to 24 hours. [15] The cell cycle arrest biomarkers tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) and insulin-like growth factorbinding protein 7 (IGFBP7) indicate G1-phase arrest due to cellular stress and are used as a combined product ([TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7]). [16] L-FABP is expressed during proximal tubular ischemia, [17] while IL-18 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine released from injured tubules. [18] C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14) is produced in high levels in sustained inflammation and is a prognostic marker for persistent AKI. [19] Furthermore, it is a prognostic marker for persistent AKI (≥48 hours), and its optimal cutoff is ≥13 ng/mL. [19] The pooled diagnostic characteristics of these biomarkers are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Diagnostic performance of key and emerging AKI biomarkers (Pooled 2024–2025 data)

Multi-biomarker panels enhance diagnostic accuracy considerably. The integration of NGAL, KIM-1, and IL18 results in AUCs surpassing 0.90–0.95, improving net reclassification by 20% to 32% relative to SCr alone. [10] The integration of machine learning with [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] and clinical variables enhances risk prediction, resulting in an AUC of 0.91 to 0.94. [20] Serial monitoring improves temporal resolution: increasing levels of NGAL or CCL14 signify disease progression, whereas declining levels of KIM-1 or L-FABP indicate recovery. [21]

The Lack of Standardization and Practical

Constraints Despite the persuasive diagnostic and prognostic capabilities shown in Table 1, a major obstacle to widespread clinical use is the absence of test standardization. Commercially accessible platforms for important biomarkers such as NGAL, [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7], and CCL14 may have inter-laboratory coefficients of variation of 20% to 30%. [22,23] This heterogeneity complicates the creation of universal clinical cutoffs, necessitating that reference values and interpretations be tailored to the individual test and demographic context, particularly in patients with pre-existing CKD, where baseline levels of KIM-1 may be increased. [24] To address this critical barrier, global standardization efforts are underway. The Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) has published consensus recommendations on AKI biomarker use and validation. [6] Furthermore, a collaborative Biomarker Standardization Initiative is in development, aiming to unify assay calibration, establish universal reference materials, and define context-specific cutoffs across different platforms and populations.

Emerging Mechanistic Classes of AKI Biomarkers

In addition to recognized indicators of tubular injury and cellcycle arrest, various other pathophysiological markers have been identified as potential early diagnostic and prognostic tools, as detailed by Yang et al. [10]

Biomarkers of Renal Tubular Filtration

• Cystatin C (CysC) and Proenkephalin A (PENK): CysC and PENK function as real-time indicators of glomerular filtration, independent of muscle mass. Urinary CysC levels increase within 0 to 12 hours following cardiac surgery (AUC: 0.86). In contrast, high plasma PENK levels are associated with a doubling of the risk of AKI for each logarithmic increase in sepsis and heart failure cohorts. [10]

• Clinical utility: They enable enhanced preoperative risk stratification (eGFR-CysC <90 mL/min/1.73 m²) and early detection in sarcopenic and elderly patients.

Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

Biomarkers of oxidative stress measure the imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses. ROS, produced during events like ischemia-reperfusion, provides early insight into injury severity and potential reversibility with antioxidant therapy. [10]

• Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1):

― Urinary SOD1: Indicates intracellular release from damaged proximal tubular cells. In cardiothoracic surgery patients, urinary SOD1 levels rise within 6 to 12 hours and predict AKI with an AUC of 0.85, outperforming NGAL in some cohorts. [10]

― Erythrocyte SOD1 activity: A systemic marker of antioxidant capacity. In septic shock, low erythrocyte SOD1 activity (<3.32 U/mg Hb) at ICU admission independently predicts AKI development (AUC: 0.69) and identifies patients at risk for persistent kidney failure. [10]

• Clinical implication: Dual measurement (elevated urinary SOD1 + decreased erythrocyte SOD1 activity) signals both local tubular injury and systemic oxidative collapse, potentially guiding early initiation of antioxidant strategies (e.g., N-acetylcysteine, vitamins C and E) in high-risk surgical or septic patients.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

• Serum miR-21 and exosomal miR210/320/184/6766-3p levels increase within hours in ischemic, septic, and contrast-induced AKI. [10] • Advantages: They are stable in biofluids, amenable to multiplexing, and have potential as anti-miR therapeutics.

Biomarkers of Renal Inflammation and Repair

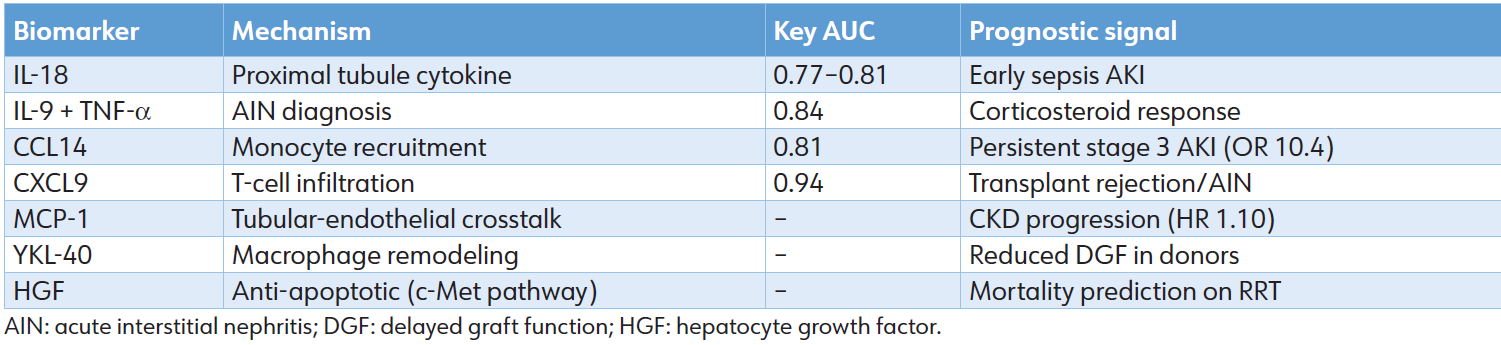

A spectrum of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors captures the transition from injury to resolution. Integration: CCL14 and CXCL9 are FDA-cleared; multi-marker inflammation scores outperform single analytes in pediatric and transplant cohorts. Despite strong performance, challenges persist. Cutoff values differ based on assay, population, and comorbid conditions; systemic inflammation complicates the interpretation of NGAL in sepsis, whereas baseline CKD increases KIM-1 levels. Standardization efforts, including the development of point-of-care platforms, are in progress to enable real-time application. [25] These biomarkers have shifted the diagnosis of AKI from an emphasis on functional loss to a focus on molecular injury, facilitating etiology-specific applications (Table 2).

Table 2: Inflammation/repair biomarkers

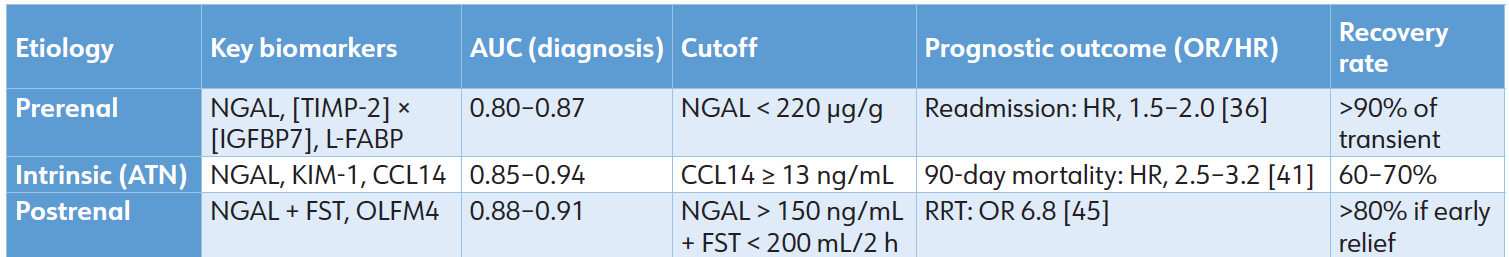

The varied pathophysiology of AKI, which includes prerenal hypoperfusion, intrinsic parenchymal damage, and postrenal obstruction, necessitates etiology-specific analysis of biomarkers. [3] Functional markers, such as SCr, exhibit uniform increases, whereas novel damage and stress biomarkers display varying kinetics: minimal in pure prerenal conditions, significant in intrinsic injury, and inconsistent in obstruction-induced AKI. [25] This differential expression enables subphenotyping, risk stratification, and precision therapy, carrying prognostic implications for mortality, RRT, persistent AKI, and progression to CKD. [26,27]

Prerenal AKI: Functional Stress and Reversible Injury

Prerenal AKI constitutes 40% to 60% of cases and is associated with conditions such as hypovolemia, heart failure, sepsis-induced underperfusion, and hepatorenal syndrome. It is defined by diminished renal perfusion in the absence of structural damage. [28] Novel biomarkers of tubular damage are generally low or only temporarily elevated in reversible cases, assisting in the differentiation from intrinsic AKI. [29] For instance, a urinary NGAL/creatinine ratio below 194 to 220 μg/g is predictive of terlipressin efficacy in patients with liver cirrhosis and AKI hepatorenal syndrome. [30] A [TIMP2]×[IGFBP7] value exceeding 0.3 (ng/mL)²/1000 during fluid resuscitation signifies progression to intrinsic damage (AUC: 0.87), providing insights into decongestion safety in heart failure. [31] On the other hand, L-FABP and soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) are predictive markers for transient acute AKI during diuresis, with no associated increase in mortality. [32]

Low levels of baseline damage markers, such as NGAL and KIM-1, indicate a greater than 90% probability of complete recovery within 48 hours. [33] Their sustained elevation, despite hemodynamic optimization, correlates with a heightened risk of 30-day readmission (HR: 1.5–2.0) and CKD (OR: 1.8). [34] In sepsis, plasma PENK levels correlate with mortality in overt AKI (HR: 2.1), enabling early intervention. [35]

Intrinsic AKI: Tubular Damage and Inflammation

Intrinsic AKI accounts for 30% to 50% of cases and encompasses ATN due to ischemia, sepsis, or nephrotoxins such as contrast agents and cisplatin, as well as AIN and glomerulonephritis, which result in significant biomarker release. [36] NGAL, KIM1, and L-FABP levels increase substantially within 2 to 6 hours in ATN, exhibiting an AUC of 0.85 to 0.92 compared to prerenal conditions. Notably, NGAL demonstrates an AUC of 0.82 for predicting RRT in sepsis-associated ATN. [37] In AIN, IL-9 and CXCL9 demonstrate an AUC of 0.94 for diagnostic purposes and predicting corticosteroid response. [38] A CCL14 level of ≥ 13 ng/mL is a significant predictor of persistent stage 3 AKI in ICU populations (OR: 10.4). [19]

This has notable prognostic implications, including increased non-recovery rates (30%–40%) and progression of CKD (HR: 1.8–3.2). [39] The upper tertile of NGAL correlates with a hazard ratio of 2.5 for 90-day mortality, whereas KIM-1 levels exceeding 2.0 ng/mL are predictive of major adverse kidney events, demonstrating an area under the curve of 0.88. [40] Applying biomarkers to guide the avoidance of nephrotoxins results in a 25% reduction in the severity of AKI in cases of cisplatin-induced damage. [41]

Postrenal AKI: Obstruction and Recovery Potential

Postrenal AKI (accounting for 5% to 10% of cases), caused by urinary tract blockage, is mostly detected using imaging techniques. [42] Biomarkers assist in evaluating the severity of harm and the likelihood of recovery after the alleviation of blockage. NGAL and [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] exhibit moderate elevations; when coupled with a furosemide stress test, NGAL >150 ng/mL and FST output <200 mL/2 h forecast the need for RRT (AUC: 0.91). [43] Olfactomedin-4 (OLFM4) signifies furosemide unresponsiveness with 88% specificity. [44]

The prognostic importance is contingent upon the time of biomarker normalization. Delayed normalization correlates with a longer hospital stay and advancement to chronic kidney injury if NGAL exceeds 500 ng/mL at 72 hours postrelief. [45] Early intervention coupled with reduced CCL14 levels forecasts above 80% recovery (Table 3). [46]

Table 3: Etiology-specific diagnostic and prognostic performance of novel biomarkers.

In cirrhosis (a prerenal/ATN overlap), urine calprotectin (sensitivity 92%) distinguishes intrinsic damage, while NGAL <220 μg/g indicates recovery in hepatorenal syndrome. [47] Frameworks, such as LIION, integrate biomarkers with hemodynamic data to enhance the prediction of vasopressor response in sepsis, achieving an accuracy of 85%. [48] Biomarker-guided treatment bundles have shown a 20% to 30% reduction in RRT use across several etiologies. [49]

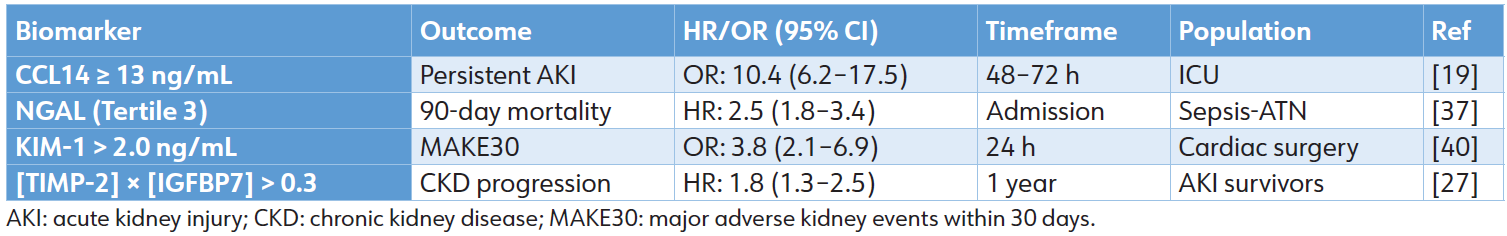

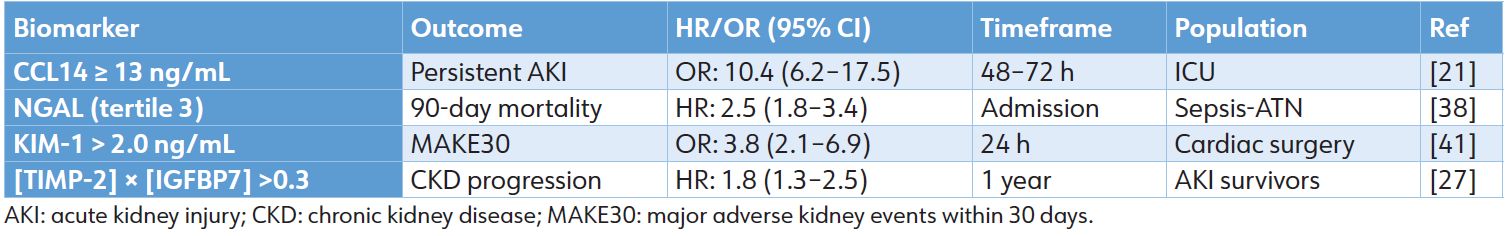

The differential expression and prognostic implications of novel biomarkers across prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal AKI etiologies underscore their potential to move beyond simple diagnosis. As demonstrated, these tools can stratify risk for recovery, dialysis dependency, progression to CKD, and mortality. The consolidated prognostic performance of leading biomarkers for these major, patient-centered clinical endpoints—persistent severe AKI, short-term mortality, major adverse kidney events, and long-term renal decline—is summarized in Table 4. This robust and validated predictive capacity confirms that biomarker-guided risk assessment is a clinical reality. However, the translation of this precise predictive power into equally effective, evidence-based therapeutic action presents the next fundamental challenge in transforming AKI management from a reactive to a precision-oriented discipline.

Table 4: Prognostic performance across key outcomes

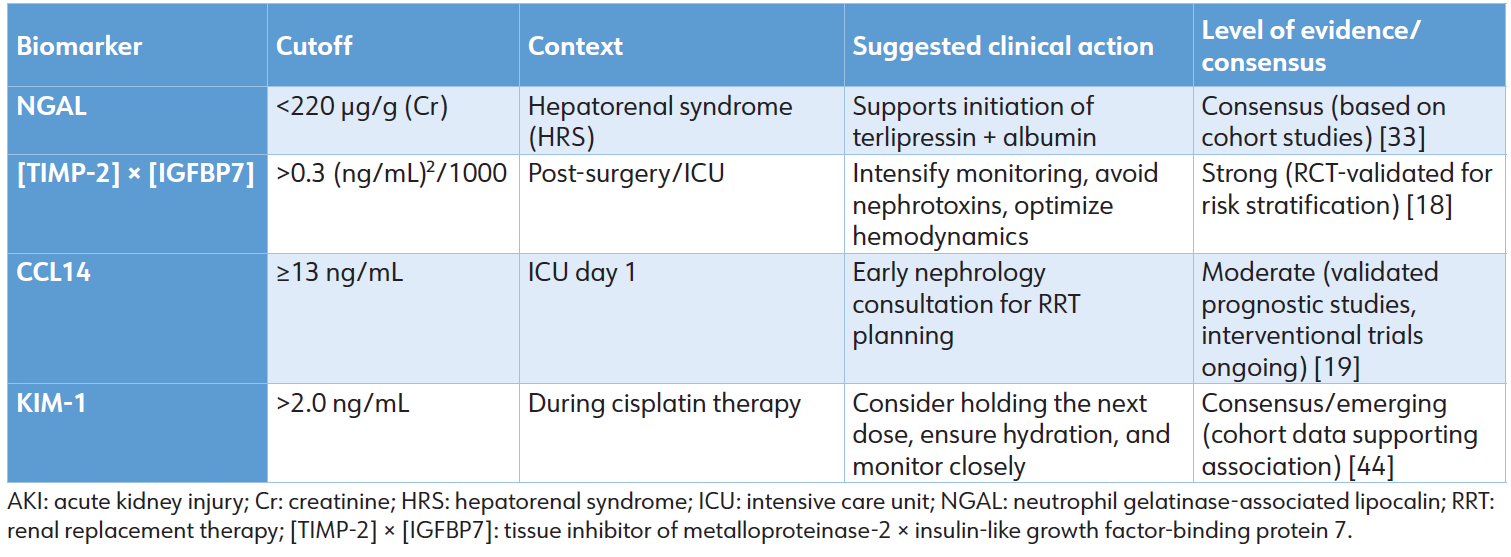

The current, consensus-driven approach to linking biomarker levels to clinical action is summarized in Table 5. These thresholds and suggested responses are derived from cohort studies and expert opinion, reflecting the interim guidance available while definitive interventional trial evidence is being generated. [33, 44] Cutoff values and suggested actions are context-specific and should be integrated with the full clinical picture. The “Level of Evidence” is based on current literature as cited.

Table 5: Summary of clinical biomarker thresholds and associated management actions.

The establishment of novel AKI biomarkers with high diagnostic and prognostic accuracy, as detailed in Sections 2 and 3, represents a paradigm shift from functional to molecular diagnostics. However, a critical translational challenge now defines the frontier of clinical implementation: the clinical action gap. This gap describes the disconnect between the robust ability of biomarkers to identify patients at high risk for severe or persistent AKI and the current lack of standardized, evidence-based therapeutic protocols triggered by these biomarker signals. [13,49] While functional markers like SCr are poor sentinels, they have historically been linked to broad interventions (e.g., fluid resuscitation, dialysis). In contrast, modern damage biomarkers offer superior early warning but have not yet been reliably paired with specific, proven treatments, leaving clinicians with heightened risk awareness but unclear management pathways.

Defining the Disconnect: Diagnostic Precision versus Therapeutic Uncertainty

The performance metrics summarized in Tables 1, 3, and 5 demonstrate that biomarkers can predict adverse outcomes— including progression to severe AKI, need for RRT, and mortality—with AUC values often exceeding 0.80 and hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) signifying substantial risk. [8,10,19] Despite this predictive power, a positive biomarker test does not inherently dictate a subsequent clinical action with the same level of evidence. This contrasts sharply with other fields, such as cardiology, where an elevated troponin level integrates seamlessly into a well-defined diagnostic and interventional algorithm for acute coronary syndrome. In AKI, the translation from a biomarker-positive state to a biomarkerguided intervention remains largely undefined, creating a barrier to realizing the promise of precision medicine.

Illustrative Examples of the Clinical Action Gap

The reality of this gap is best illustrated by examining specific, high-performance biomarkers and the clinical uncertainty that follows their elevation:

• C-C motif chemokine Ligand 14 (CCL14): A urinary CCL14 level ≥ 13 ng/mL is a highly specific predictor of persistent stage 3 AKI, with an OR of 10.4. [19] This result unequivocally identifies a patient with a high likelihood of prolonged renal failure. Yet, the appropriate clinical response remains ambiguous. Should this biomarker result prompt:

1. Immediate nephrology consultation and preemptive planning for early RRT initiation?

2. A trial of conservative, optimized supportive care while closely monitoring for traditional indications for RRT?

3. Enrollment in a clinical trial for a novel immunomodulatory or repair-promoting agent?

Currently, no consensus or high-level evidence dictates the choice, rendering this powerful prognostic tool primarily informative rather than directive.

• Cell cycle arrest biomarkers ([TIMP2]×[IGFBP7]): An elevated urinary [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] ratio (>0.3 [ng/mL]²/1000) indicates renal tubular cell cycle arrest due to stress and is a validated predictor of AKI development within 12 to 24 hours. [16,31] In a patient with hypoperfusion, a rising ratio signals the transition from prerenal azotemia to incipient intrinsic injury. However, the optimal therapeutic response is not standardized. Should the clinician:

1. Aggressively modify fluid resuscitation strategy (e.g., switch to balanced crystalloids, initiate goal-directed therapy)?

2. Immediately discontinue potential nephrotoxins or diuretics?

3. Simply intensify hemodynamic monitoring without changing management?

The biomarker pinpoints a moment of renal vulnerability, but evidence-based guidelines for the next intervention are lacking. [50]

This gap persists because the biomarker literature is predominantly composed of diagnostic accuracy and prognostic association studies. While essential, these studies do not test whether acting upon the biomarker result improves patient outcomes. The definitive step required is the design and execution of biomarker-stratified interventional trials, where a specific biomarker threshold randomizes patients to different, protocolized management strategies.

Current Efforts and the Path Forward

Initial efforts to bridge this gap have focused on biomarkerguided care bundles. Trials such as PrevAKI and BigpAK, which used [TIMP-2]×[IGFBP7] to trigger a bundle of supportive measures (e.g., hemodynamic optimization, avoidance of nephrotoxins), have demonstrated feasibility and a 15% to 30% relative reduction in moderate-severe AKI in targeted surgical populations. [49] However, the benefits in heterogeneous ICU populations have been more modest, and these bundles often represent optimized standard care rather than novel, biomarker-specific therapies. [49] The next generation of trials must move beyond generic bundles to evaluate etiology-specific and biomarker-targeted interventions. For example, a trial could randomize patients with septic AKI and high CCL14 to early versus standard RRT initiation, or those with elevated NGAL during cisplatin therapy to a protocol of hyperhydration plus novel cytoprotectants versus standard hydration alone.

Addressing this complexity—integrating multi-marker panels, serial measurements, dynamic clinical variables, and patient subphenotypes to generate actionable, real-time decisions— is a formidable challenge. It requires moving from static risk prediction to dynamic clinical decision support. This complexity sets the stage for the next critical advancement: the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to synthesize this multidimensional data and directly assist in bridging the clinical action gap.

The preceding analysis underscores that a central translational challenge obstructs the pathway from biomarker discovery to improved clinical outcomes: the “clinical action gap.” Bridging this gap through biomarker-stratified trials and intelligent clinical decision support, as outlined, is the definitive next step. However, the success of this endeavor is inextricably linked to overcoming a suite of persistent logistical, economic, and evidence-based hurdles that currently constrain even the widespread diagnostic application of these novel tools.

Foundational Barriers

Standardization, Interpretation, and Workflow Integration

A major impediment to both research and routine care is the lack of assay standardization. Commercial platforms for key biomarkers such as NGAL, [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7], and CCL14 can exhibit inter-laboratory coefficients of variation of 20% to 30%, confounding the establishment of universal diagnostic and prognostic cutoffs. [13,22] This heterogeneity necessitates context- and assay-specific reference ranges, a requirement further complicated by patient-specific factors. For instance, systemic inflammation in sepsis elevates NGAL independently of renal damage, reducing specificity, while CKD elevates baseline KIM-1 levels, diminishing its dynamic range for acute injury. [23,24] Translating biomarker signals into action within the clinical workflow presents another layer of complexity. Integration with electronic health records (EHRs) and clinical decision support systems remains nascent, with fewer than 10% of centers routinely employing biomarkers outside research protocols. [55] The development of rapid, point-of-care platforms is progressing, with the [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] test being a notable FDA-cleared example; [51] however, scalable systems for other biomarkers like NGAL and CCL14 are still under development. Global standardization initiatives, such as those proposed by the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI), are critical to unify assays, establish reference materials, and enable the multicenter trials required to close the action gap. [6]

Economic and Equity Imperatives

The cost-effectiveness of biomarker-guided care is a pivotal consideration for health systems. While interventions based on [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] have reduced severe AKI in targeted surgical cohorts, the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year may be prohibitive in general, unselected ICU populations, with estimates potentially exceeding $50,000. [54] Comprehensive cost-utility analyses that account for long-term benefits, such as the prevention of CKD, are urgently needed. Equally critical is the issue of equitable access. The burden of AKI is highest in low-resource settings, where mortality rates can surpass 50%, yet access to advanced biomarker testing is most limited. [1,22] This disparity risks widening global health inequities. Promising developments in microfluidic and smartphone-based assay technologies aim to deliver low-cost, point-of-care testing, which could democratize access and enable biomarker-guided care in diverse healthcare environments. [52]

Evidence Gaps and Inclusivity in Future Research

Substantial evidential deficiencies must be addressed to ensure biomarker utility across the entire AKI spectrum. Key populations remain underrepresented: postrenal (obstructive) AKI constitutes fewer than 5% of validation cohorts, leaving the dynamics of biomarker release and recovery after obstruction relief poorly defined. [45] Pediatric data, while robust for NGAL post-cardiac surgery, are lacking for multi-marker panels in sepsis or nephrotoxin exposure. [56] Long-term prognostic validation (>1 year) for emerging markers of oxidative stress (e.g., SOD1), microRNAs, and repair (e.g., YKL-40, HGF) is limited, particularly in nonCaucasian demographics. [10] Future research must be deliberately inclusive, targeting these populations to ensure that the precision medicine paradigm does not exacerbate existing evidence gaps but rather benefits all patient groups.

Synthesis and Integrated Future Pathways

The integration of AI, as discussed in Section 5, presents a powerful solution to synthesize multi-marker data, clarify etiology, and generate explainable clinical recommendations, directly addressing the complexity that underpins the action gap. However, the full potential of this integration can only be realized within a supportive ecosystem. This ecosystem requires: (1) International standardization of assays and cutoffs through initiatives like the proposed Biomarker Standardization Initiative; (2) Targeted, inclusive research that fills evidence gaps in special populations and focuses on biomarker-guided therapeutic trials; (3) Development of cost-effective, equitable point-of-care technologies to ensure global applicability; and (4) Optimized regulatory pathways for the evaluation and approval of multi-marker panels and AI-augmented diagnostic tools. The convergence of these elements will transition AKI care from a reactive model anchored by SCr to a proactive, precision-oriented strategy where molecular diagnosis seamlessly informs timely, effective intervention, ultimately preserving renal function and improving long-term survival.

The incorporation of new biomarkers in AKI management signifies a significant transition from functional to molecular diagnostics. However, their ultimate clinical impact is still under continuous assessment. Meta-analyses indicate improved early detection (AUC: 0.80–0.95) and prognostic stratification across various etiologies; nonetheless, the extent of outcome enhancement in unselected populations is often modest. Randomized trials such as PrevAKI and BigpAK indicate a 15% to 30% reduction in severe AKI among high-risk surgical patients. At the same time, the benefits observed in general ICU populations are less pronounced and occasionally non-significant. [49] This discrepancy highlights a core challenge: biomarkers suggest risk but do not inherently determine therapy. Without standardized, evidence-based response protocols similar to troponin-guided algorithms in acute coronary syndrome, their application remains primarily limited to risk prediction.

A second area of debate pertains to subphenotyping. Prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal AKI should be viewed as a continuum rather than as separate categories. Low NGAL levels in hypovolemia may suggest reversible stress; however, comparable levels in early sepsis could obscure the onset of ATN. [48] Frameworks such as LIION and the furosemide stress test seek to tackle this issue; however, they necessitate prospective validation. [48] The association of persistent CCL14 elevation with non-recovery raises questions regarding the optimal clinical response, including the initiation of early RRT, conservative management, or immunomodulation, which remains uncertain. [19] These uncertainties underscore the necessity for therapeutic trials informed by biomarkers, rather than solely relying on diagnostic studies.

Equitable access is a critical issue. The [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] point-of-care test is FDA-approved; [13,51] however, it is expensive and frequently unavailable in low-resource countries, [6] settings where mortality rates for AKI can surpass 50%. [22] Emerging microfluidic and smartphone-based assays present significant potential; however, substantial regulatory and scalability challenges exist (Table 6). [52]

Table 6: Prognostic performance across key outcomes.

Besides their robust diagnostic and prognostic efficacy, the widespread use of new AKI biomarkers encounters several obstacles and limitations. Assay variability presents a significant challenge, since commercial platforms for NGAL, [TIMP-2]×[IGFBP7], and CCL14 have inter-laboratory coefficients of variation of 20% to 30%, hence, confounding the determination of universal cutoffs. [13,53] Populationspecific thresholds complicate interpretation; pediatric, geriatric, and CKD groups need tailored reference ranges, for which no agreement has been established. Systemic inflammation during sepsis increases NGAL levels regardless of renal damage, diminishing the specificity and resulting in false-positive rates of 15% to 25%. Similarly, elevated baseline KIM-1 levels in CKD reduce its dynamic range. [24]

Cost-effectiveness is another difficulty. Although [TIMP-2] + [IGFBP7] decreases the occurrence of severe AKI by 15% to 25% in high-risk surgical cohorts, the additional cost per quality-adjusted life year may surpass $50,000 in general ICUs. [54] Point-of-care testing shows potential but is now restricted to [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] with a 20-minute turnaround time. Scalable systems for NGAL and CCL14 are in advanced stages of development. Integration with EHRs and clinical decision support systems is still in its infancy, with less than 10% of centers routinely using biomarkers outside of clinical trials. [55] Equitable access remains a critical challenge, as advanced biomarker testing is often unavailable in lowresource settings where the burden of AKI is highest. Emerging point-of-care (e.g., cartridge-based [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] test) and microfluidic or smartphone-based assays for NGAL and CCL14 show significant promise for reducing this diagnostic inequity. These technologies aim to deliver rapid, low-cost, and minimally invasive testing, potentially enabling biomarker-guided care in diverse healthcare environments.

Substantial evidential deficiencies remain. Postrenal AKI is inadequately represented in validation studies, accounting for fewer than 5% of biomarker cohorts. The dynamics of obstructive damage and recovery forecasting need targeted experiments. [45] Pediatric data are comprehensive for NGAL after heart surgery, but are deficient in multi-marker panels for sepsis or nephrotoxin exposure. [56] Prolonged prognostic validation (exceeding one year) for SOD1, microRNA, and repair biomarkers (YKL-40, HGF) is constrained, particularly in non-Caucasian demographics and resource-limited environments. [10]

Emerging paradigms, especially the incorporation of AI, offer potential remedies to existing constraints. For clinical trust and adoption, these systems must progress beyond a “black box” model. Future AI platforms must be explainable, providing not only a risk score (e.g., AUCs of 0.92–0.95 for AKI onset) but also elucidating the contributing factors. For example, a ‘high risk for RRT is driven by the combination of CCL14 ≥13 ng/mL, a 40% rise in SCr, and persistent hypotension’. [20] Powerful systems will integrate multi-marker panels (e.g., [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7], NGAL) with essential clinical variables (e.g., vasopressor dose, fluid balance, comorbidities) to develop transparent, actionable algorithms. This method enhances multi-omics strategies that reveal subphenotype-specific signatures, as demonstrated by the LIION clusters, thereby advancing precision medicine in AKI. [57]

Standardized reporting frameworks, such as the planned Biomarker Standardization Initiative, seek to unify cutoffs and assay calibration. [6] Future directions should emphasize:

Extensive randomized controlled trials: To evaluate biomarker-directed intervention bundles (e.g., NGAL with FST in obstructive AKI, CCL14 for RRT weaning) across various patient populations.

Global validation studies: Especially in low-resource environments, where the incidence of AKI is most pronounced and access to sophisticated diagnostics is restricted. Comprehensive cost-utility analyses: These include longterm outcomes, including the mitigation of CKD development.

Optimized regulatory pathways: To expedite the approval and deployment of multi-marker panels and AI-augmented diagnostic instruments.

The emergence of new biomarkers, however diagnostically potent, poses a barrier to clinical integration. Section 3.4 identifies the “clinical action gap,” which underscores the challenge of converting various biomarker data into targeted, evidence-based therapies. AI and ML are emerging as revolutionary instruments to navigate this complexity, bridging biomarker discovery with precise therapeutic intervention. [20]

From Prediction to Proactive Risk Stratification

Although individual biomarkers have predictive significance, their full potential is seen when combined with the extensive data inside the EHR. Machine learning algorithms may incessantly evaluate dynamic variables, such as vital signs, drug exposure, fluid balance, comorbidities, and sequential biomarker measurements, to provide real-time, individualized risk ratings. This transition from static to dynamic prediction is already being realized in clinical settings. For instance, commercial EHR systems have begun embedding real-time AKI prediction models, such as the widely deployed Epic EHR’s AKI Risk Model, which continuously analyzes patient data to flag high-risk individuals hours before a creatinine rise. Similarly, research initiatives like the DeepAISE algorithm have been integrated into pilot ICU dashboards, demonstrating improved early detection by synthesizing complex vital sign and laboratory trends. [20] These models surpass static prediction by detecting individuals at elevated risk for AKI hours to days before an increase in blood creatinine, with reported AUCs ranging from 0.92 to 0.95. [20] This offers a vital opportunity for proactive action, such as the prompt cessation of nephrotoxins or enhanced hemodynamic control.

Enabling AKI Subphenotyping and Etiology Clarification

AKI is a diverse condition, and the etiology-specific biomarker patterns outlined in Section 3 signify progress towards precision treatment. AI expedites this process via unsupervised learning to identify new subphenotypes of AKI that are undetected by doctors. For example, models may discern specific clusters of septic AKI patients by analyzing unique combinations of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., IL18, CCL14), cell cycle arrest indicators ([TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7]), and clinical characteristics. [48] These subphenotypes have shown a correlation with varied therapeutic responses and significantly disparate results, facilitating the initiation of focused treatment studies.

Bridging the Clinical Action Gap With Explainable AI

A fundamental obstacle to the clinical adoption of AI is the “black box” problem, where the model’s reasoning is opaque and not easily interpretable by clinicians. [58] This issue is being addressed through the development of Explainable AI (XAI). An effective XAI system does not merely provide a risk score; it delivers a clinically interpretable justification for that score. [20] For example, rather than a generic “high risk for RRT” alert, an XAI system could generate an output such as: “High risk (94%) for persistent AKI requiring RRT. Key drivers: CCL14 ≥ 13 ng/mL, [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] ratio >2.0, and sustained hypotension requiring norepinephrine >0.1 mcg/kg/min. Suggested actions: (1) Prompt nephrology consultation, (2) evaluate early RRT planning, and (3) avoid fluid overload. This approach transforms biomarkers from isolated numerical values into components of a pragmatic clinical decision support system, directly addressing the action gap by proposing context-aware interventions. [59]

A fundamental obstacle to the clinical adoption of AI is the “black box” problem, where the model’s reasoning is opaque and not easily interpretable by clinicians. [58] This issue is being tackled via the development of Explainable AI (XAI). An XAI system not only provides a risk score; it offers a clinically interpretable justification. For instance, rather than a vague “high risk for RRT” notification, the system may delineate: High risk (94%) for prolonged AKI necessitating RRT. Key determinants: CCL14 ≥ 13 ng/mL, [TIMP-2]×[IGFBP7] ratio >2.0, and sustained hypotension necessitating norepinephrine >0.1 mcg/kg/min. Suggested measures: (1) Prompt nephrology consultation, (2) evaluate early RRT planning, and (3) prevent fluid excess [20]. This converts biomarkers from mere numerical values into elements of a pragmatic clinical decision support system, directly tackling the action gap.

Future Directions and Challenges

The amalgamation of AI with AKI biomarkers presents several obstacles. Future endeavors should concentrate on the anticipated validation of AI-directed intervention bundles in randomized controlled trials. Moreover, guaranteeing algorithmic fairness and generalizability across varied populations and healthcare environments is essential. The advancement of seamless EHR integration and effective point-of-care biomarker testing systems is crucial for realizing AI-driven precision nephrology at the bedside.

The identification of novel biomarkers is revolutionizing the management of AKI, facilitating early detection of subclinical damage and accurate prognostic stratification across various etiologies. In contrast to the delayed response of SCr, these biomarkers enable prompt intervention, informing fluid management, nephrotoxin avoidance, and obstruction relief. Multi-marker panels and serial monitoring enhance risk stratification for the progression to CKD, dialysis, or mortality. Overcoming challenges related to standardization, validation, and cost is essential for completing the transition to routine practice. The incorporation of these tools with point-of-care testing and explainable AI into EHRs will initiate a new phase in precision nephrology. Ultimately, the future success of this paradigm depends on systematically closing the clinical action gap through biomarker-guided randomized controlled trials and the intelligent integration of AI. This paradigm promises not only enhanced diagnosis but also the prevention of AKI, which would preserve renal function and improve long-term survival.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the developers of the large language model, which assisted in the drafting and structuring of this manuscript through interactive dialogue and synthesis of scientific concepts. All content was critically reviewed and verified by the authors. The authors acknowledge the support from Qatar National Library for paying article-processing charges after acceptance.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors have significantly contributed to the work, whether by conducting literature searches, drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article. They have given their final approval of the version to be published, have agreed with the journal to which the article has been submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

References

1. Hoste EAJ, Kellum JA, Selby NM, Zarbock A, Palevsky PM, Bagshaw SM, et al. Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(10): 607-625.

2. Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfaraj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, et al. World incidence of AKI: A metaanalysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(9):1482-1493.

3. Chawla LS, Bellomo R, Bihorac A, Goldstein SL, Siew ED, Bagshaw SM, et al; Acute Disease Quality Initiative Workgroup 16. Acute kidney disease and renal recovery: Consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(4): 241-257.

4. Ostermann M, Joannidis M. Acute kidney injury 2016: Diagnosis and diagnostic workup. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):299.

5. See EJ, Jayasinghe K, Glassford N, Bailey M, Johnson DW, Polkinghorne KR, et al. Long-term risk of adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies using consensus definitions of exposure. Kidney Int. 2019;95(1):160-172.

6. Ostermann M, Zarbock A, Goldstein S, Kashani K, Macedo E, Murugan R, et al. Recommendations on acute kidney injury biomarkers from the Acute Disease Quality Initiative consensus conference: A consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019209.

7. Haase M, Bellomo R, Devarajan P, Schlattmann P, Haase-Fielitz A; NGAL Meta-analysis Investigator Group. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in diagnosis and prognosis in acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(6):1012-1024.

8. Matarneh A, Akkari A, Sardar S, Salameh O, Dauleh M, Matarneh B, et al. Beyond creatinine: Diagnostic accuracy of emerging biomarkers for AKI in the ICU - A systematic review. Ren Fail. 2025;47(1):2556295.

9. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):1-138.

10. Yang H, Chen Y, He J, Li Y, Feng Y. Advances in the diagnosis of early biomarkers for acute kidney injury: A literature review. BMC Nephrol. 2025;26(1):115.

11. Murray PT, Mehta RL, Shaw A, Ronco C, Endre Z, Kellum JA, et al. Potential use of biomarkers in acute kidney injury: Report and summary of recommendations from the 10th Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative consensus conference. Kidney Int. 2014;85(3):513-521.

12. Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T, Artigas A, Bagshaw SM, Bell M, et al. Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):R25.

13. Albert C, Haase M, Albert A, Kropf S, Bellomo R, Westphal S, et al. Biomarker-guided risk assessment for acute kidney injury: Time for clinical implementation? Ann Lab Med. 2021;41(1):1-15.

14. Haase M, Devarajan P, Haase-Fielitz A, Bellomo R, Cruz DN, Wagener G, et al. The outcome of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin-positive subclinical acute kidney injury: A multicenter pooled analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(17):1752-1761.

15. Han WK, Waikar SS, Johnson A, Betensky RA, Dent CL, Devarajan P, et al. Urinary biomarkers in the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2008;73(7): 863-869.

16. Kellum JA, Chawla LS. Cell-cycle arrest and acute kidney injury: The light and the dark sides. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(1):16-22.

17. Xu Y, Xie Y, Shao X, Ni Z, Mou S. L-FABP: A novel biomarker of kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;445:85-90.

18. Lin X, Yuan J, Zhao Y, Zha Y. Urine interleukin-18 in prediction of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2015;28(1):7-16.

19. Bagshaw SM, Al-Khafaji A, Artigas A, Davison D, Haase M, Lissauer M, et al. External validation of urinary C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14) for prediction of persistent acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):185.

20. Koozi H, Engström J, Friberg H, Frigyesi A. Explainable AI identifies key biomarkers for acute kidney injury prediction in the ICU. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2025;13(1):106. 21. Horie R, Hayase N, Asada T, Yamamoto M, Matsubara T, Doi K. Trajectory pattern of serially measured acute kidney injury biomarkers in critically ill patients: A prospective observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):84.

22. Parikh CR. A point-of-care device for acute kidney injury: A fantastic, futuristic, or frivolous ‘measure’? Kidney Int. 2009;76(1):8-10.

23. Nguyen MT, Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008; 23(12):2151-2157.

24. Sandokji I, Greenberg JH. Plasma and urine biomarkers of CKD: A review of findings in the CKiD study. Semin Nephrol. 2021;41(5):416-426.

25. Makris K, Spanou L. Acute kidney injury: Diagnostic approaches and controversies. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016;37(4):153-175.

26. Kellum JA, Prowle JR. Paradigms of acute kidney injury in the intensive care setting. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(4):217-230.

27. Bhatraju PK, Zelnick LR, Chinchilli VM, Moledina DG, Coca SG, Parikh CR, et al. Association between early recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury and long-term clinical outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202682.

28. Legrand M, Rossignol P. Cardiovascular consequences of acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23): 2238-2248.

29. Nejat M, Pickering JW, Walker RJ, Endre ZH. Urinary cystatin C is diagnostic of acute kidney injury and sepsis, and predicts mortality in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R85.

30. Gambino C, Piano S, Stenico M, Tonon M, Brocca A, Calvino V, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in patients with cirrhosis and acute kidney injury. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1630-1638.

31. Erstad BL. Usefulness of the biomarker TIMP-2•IGFBP7 for acute kidney injury assessment in critically ill patients: A narrative review. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;56(1):83-92.

32. Doi K, Noiri E, Maeda-Mamiya R, Ishii T, Negishi K, Hamasaki Y, et al. Urinary L-type fatty acid-binding protein as a new biomarker of sepsis complicated with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10): 2037-2042.

33. Koyner JL, Garg AX, Coca SG, Sint K, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Patel UD, et al. Biomarkers predict recovery from acute kidney injury: The TRIBE-AKI consortium. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2151-2159.

34. James MT, Levey AS, Tonelli M, Tan Z, Barry R, Pannu N, et al. Incidence and prognosis of acute kidney injuries in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2023;147(11):867-879.

35. von Groote T, Albert F, Meersch M, Koch R, Porschen C, Hartmann O, et al. Proenkephalin A 119-159 predicts early and successful liberation from renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: A post hoc analysis of the ELAIN trial. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):333.

36. Zarbock A, Nadim MK, Pickkers P, Gomez H, Bellomo R, Legrand M, et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: Consensus report of the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(6): 401-417.

37. de Geus HR, Bakker J, Lesaffre EM, le Noble JL. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin at ICU admission predicts for acute kidney injury in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):907-914.

38. Moledina DG, Wilson FP, Pober JS, Perazella MA, Singh N, Luciano RL, et al. Urine TNF-α and IL-9 for clinical diagnosis of acute interstitial nephritis. JCI Insight. 2019;4(10):e127456.

39. Pannu N, James M, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Association between AKI, recovery, and long-term outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(1):21-28.

40. Coca SG, Nadkarni GN, Garg AX, Koyner J, ThiessenPhilbrook H, McArthur E, et al. Urinary, plasma, and composite biomarkers for AKI after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34(8):1378-1390.

41. Ostermann M, Legrand M, Meersch M, Srisawat N, Zarbock A, Kellum JA. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury. Ann Intensive Care. 2024;14(1):145.

42. Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: The multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(8):1411-1423.

43. Chen JJ, Kuo G, Hung CC, Lin YF, Chen YC, Wu VC, et al. Furosemide stress test and biomarkers in predicting acute kidney injury outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2024;52(7): 1045-1055.

44. Xu K, Rosenstiel P, Paragas N, Hinze C, Gao X, Tian S, et al. Unique transcriptional programs identify subtypes of AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34(6):991-1006.

45. Singer E, Schrezenmeier EV, Elger A, Seelow ER, Krannich A, Luft FC, et al. Urinary NGAL-positive acute kidney injury and poor long-term outcomes in hospitalized patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1(3):114-124.

46. Qian BS, Jia HM, Weng YB, Li XC, Chen CD, Guo FX, et al. Analysis of urinary C-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CCL14) and first-generation urinary biomarkers for predicting renal recovery from acute kidney injury: A prospective exploratory study. J Intensive Care. 2023;11(1):11.

47. Allegretti AS, Ortiz G, Wenger J, Deferio JJ, Wibecan J, Kalim S, et al. Prognosis of acute kidney injury and hepatorenal syndrome in patients with cirrhosis: A prospective cohort study. Int J Nephrol. 2015;2015: 108139.

48. Wiersema R, Jukarainen S, Vaara ST, Poukkanen M, Lakkisto P, Wong H, et al. Two subphenotypes of septic acute kidney injury are associated with different 90-day mortality and renal recovery. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):150.

49. von Groote T, Meersch M, Romagnoli S, Ostermann M, Ripollés-Melchor J, Schneider AG, et al. Biomarkerguided intervention to prevent acute kidney injury after major surgery (BigpAK-2 trial): Study protocol for an international, prospective, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2023;13(3):e070240.

50. Guzzi LM, Bergler T, Binnall B, Engelman DT, Forni L, Germain MJ, et al. Clinical use of [TIMP-2]•[IGFBP7] biomarker testing to assess risk of acute kidney injury in critical care: Guidance from an expert panel. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):225.

51. Vijayan A, Faubel S, Askenazi DJ, Cerda J, Fissell WH, Heung M, et al. Clinical use of the urine biomarker [TIMP2] × [IGFBP7] for acute kidney injury risk assessment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(1):19-28.

52. Liu Y, Zhao X, Liao M, Ke G, Zhang XB. Point-of-care biosensors and devices for diagnostics of chronic kidney disease. Sens Diagn. 2024;3:1789-1806.

53. Baker TM, Bird CA, Broyles DL, Klause U. Determination of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (uNGAL) reference intervals in healthy adult and pediatric individuals using a particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay. Diagnostics (Basel). 2025;15(1):95.

54. Meersch M, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, Rossaint J, Görlich D, Stege D, et al. Validation of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers for acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110865.

55. Stanski N, Menon S, Goldstein SL, Basu RK. Integration of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin with serum creatinine delineates acute kidney injury phenotypes in critically ill children. J Crit Care. 2019;53:1-7.

56. Meena J, Thomas CC, Kumar J, Mathew G, Bagga A. Biomarkers for prediction of acute kidney injury in pediatric patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38(10):3241-3251.

57. Gerhardt LMS, McMahon AP. Multi-omic approaches to acute kidney injury and repair. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2021;20:100344.

58. Samek W, Wiegand T, Müller KR. Explainable artificial intelligence: Understanding, visualizing and interpreting deep learning models [preprint]. arXiv. 2017;1708. 08296.

59. Amann J, Blasimme A, Vayena E, Frey D, Madai VI; Precise4Q consortium. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):310.